Could Compute Become a Commodity? Lessons from Oil, Power, and Spectrum

Compute is messy and local, but if we can standardize the key dimensions just enough, markets can handle the rest.

There is a big problem with compute. If you want serious compute capacity today (whether GPUs for training or CPUs for inference), you’re making phone calls. You get a price card from AWS or a specialized provider like CoreWeave, negotiate an SLA that doesn’t port to anyone else, and hope the terms hold when you need to scale. There’s no ticker, no clearing price, no easy way to comparison-shop. It works, but it’s slow, opaque, and hard to hedge.

Bloomberg’s Felix Salmon argues that compute needs transparent pricing and liquid markets to facilitate transactions, suggesting that “making compute liquid and adding futures markets will expand investment, increase competition and rationalize AI demand.” And it may no longer be theoretical: Paul Milgrom, the Nobel Prize-winning architect of modern spectrum auctions, is working with OneChronos to build the first tradeable financial market for compute, tackling what they call “the world’s largest unhedged asset.” Meanwhile, startups like SF Compute and Compute Exchange have launched live marketplaces where buyers can rent capacity by the hour or bid in auctions.

The stakes are enormous. Recent estimates suggest up to $7 trillion in capital outlays required by 2030 to meet worldwide demand for computation. With a landscape changing this quickly (and potentially dangerously), it’s hard to know how much capital will actually be deployed once the dust settles. But even if the final value is an order of magnitude off in either direction, the world’s appetite for compute is clearly here to stay. So the question becomes: what efficiencies could a true market unlock, and can we get there without pretending compute is simpler than it really is?

The Current Landscape: Built for Relationships, Not Markets

Right now, buying compute feels more like negotiating a construction contract than trading a commodity. Hyperscalers (AWS, Azure, GCP) and specialized providers (CoreWeave, Lambda, Crusoe) quote prices based on configurations you specify: chip type, region, network topology, storage, reliability guarantees. Those quotes don’t travel well. An H100 node-hour at one provider isn’t directly comparable to an H100 node-hour at another because interconnect fabric, cooling setup, egress costs, and SLA fine print all differ.

A natural unit of trade (let’s call it a compute-hour or node-hour) is easy to define in the abstract but hard to standardize in practice. Buyers care about chip class, memory bandwidth, interconnect topology, proximity to users, power exposure, security & compliance requirements, and whether capacity is interruptible or guaranteed. Sellers care about utilization, lead time, and counterparty risk. It’s a multidimensional matching problem solved today through bespoke contracting and vendor lock-in.

Here’s the tension: buyers need heterogeneity (the right chip, in the right place, at the right time, with the right security posture), but markets prefer homogeneity (a single reference price, clear substitutes, easy resale). The question is what’s the minimum viable standardization that lets liquidity emerge without flattening what actually matters. Maybe that’s chip class plus region plus uptime tier, leaving flexibility on everything else. The goal is to standardize enough to enable trading without forcing false equivalence.

What Past Markets Can Teach

Commodities that looked hopelessly heterogeneous eventually became tradable once the right market structures emerged.

Power markets are the closest analogue. Electricity can’t be stored at scale and must be consumed instantly, making it even less fungible than compute. Yet starting in the mid-1990s, regional grid operators (PJM, ERCOT, CAISO) built spot markets, forward curves, and ancillary service auctions that let participants hedge across time and location. The key innovation was expressive bidding: participants could specify complex preferences (”I’ll supply 50 MW between 2 PM and 6 PM, but only if the price exceeds $X, and I can ramp faster if you pay me for flexibility”). PJM’s capacity auctions allocate reserves years in advance using combinatorial mechanisms that balance reliability, cost, and flexibility. The result: efficient allocation even when every megawatt has different delivery characteristics.

Oil markets faced different challenges: crude from different fields has different sulfur content, viscosity, and yield. The breakthrough came in the early 1980s with crude oil futures and the definition of deliverable grades (Brent, WTI, Dubai), letting basis differentials handle the rest. A barrel of WTI isn’t identical to Brent, but the spread between them is tradable, which means refiners can hedge feedstock risk and producers can lock in future prices.

Spectrum auctions showed how to allocate interdependent assets when bundles matter more than individual pieces. Beginning with the FCC’s first auctions in 1994, governments moved away from administrative allocation toward letting bidders express preferences across frequencies, geographies, and license types. Over the 2000s and 2010s, Paul Milgrom’s team at Auctionomics refined these combinatorial mechanisms, enabling complex reallocations like moving TV broadcasters to free up spectrum for wireless carriers. That same expressive-bidding framework is now being applied to compute. Whether it can handle compute’s heterogeneity remains to be seen, but the approach is promising.

The throughline: expressive auctions can bridge the gap between messy reality and tradable exposure. If participants can bid on bundles, substitutes, and conditional trades, the clearing mechanism can find efficient allocations without forcing everything into a single SKU.

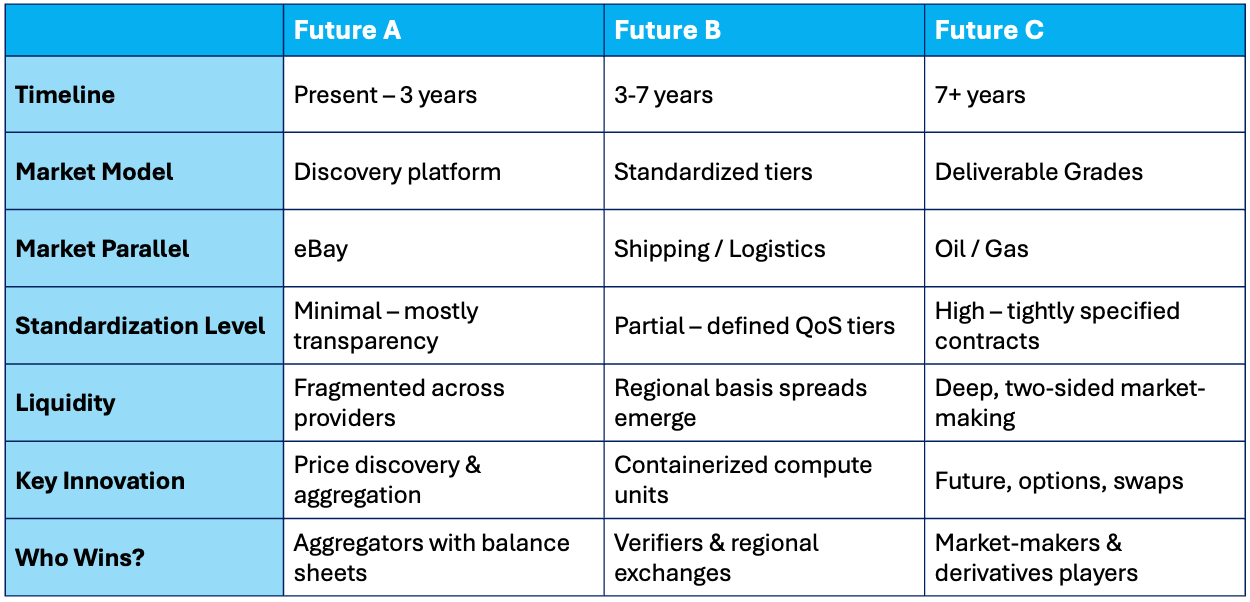

Three Futures to Explore

What might a compute market actually look like? Here are three plausible paths, each borrowing from a different industry playbook.

Future A: Minimal Standardization, Pure Matching

Think eBay for compute: a discovery platform where buyers and sellers post bids and offers, filtering by chip type, region, duration, and price. Heterogeneity persists but at least there’s transparency. This could emerge within 2-3 years as platforms like OneChronos launch and early participants test price discovery.

Value accrues to aggregators who wrap complexity into simple products. An aggregator might buy compute from dozens of providers, hold inventory risk, and sell standardized bundles with guaranteed uptime and flexible resale terms. SF Compute and Compute Exchange are early examples: the former offers hourly rentals with resale options, the latter runs periodic auctions for price discovery. The limitation across all models: liquidity stays fragmented, making deep order books difficult. But it’s a practical starting point.

Pictured: Real-time pricing from SF Compute (left) and Compute Exchange (right)

Future B: Partial Commoditization

This looks more like shipping and logistics: standardized containers (compute units with defined QoS tiers) differentiated by route, port, and carrier. A “containerized compute-hour” might specify chip class, minimum interconnect speed, and reliability tier, but leave flexibility on exact hardware and data center. Regional SKUs emerge (US-East, US-West, EU, APAC) and basis spreads between them become tradable. This is a 5-7 year horizon as standards bodies and clearing infrastructure mature.

The analogy works because shipping isn’t fully fungible either. A container from Shanghai to Long Beach isn’t the same as one from Rotterdam to New York, but the container itself is standardized, and shippers can hedge freight rate exposure. Compute could follow the same path: define tiers, set verification and SLA standards, and let regional exchanges handle the rest. In this world, verification and clearing infrastructure matter more than marketing.

Future C: High Commoditization

This is the fully financialized endgame, where compute trades like oil or natural gas. Deliverable grades are tightly specified: “A-class FP8 GPU-hour, ≥80GB HBM3, ≥400 Gbps intra-node interconnect, US-East-1 zone, 99% uptime.” Substitution bands are clear. Futures, options, and swaps reference those grades, and market-makers provide two-sided liquidity. This is a decade-plus vision requiring deep liquidity and regulatory clarity.

Imagine a hedge fund betting on tightening compute supply six months out. It buys compute futures, delta-hedges with power forwards (since compute costs correlate with electricity prices), and sells volatility to data centers wanting predictable budgets. Or picture a hyperscaler offering “compute weather derivatives” the way utilities sell heating-degree-day contracts: pure financial exposure, no physical delivery required.

The unlock here is real hedging: AI labs can lock in training costs a year in advance; data center developers can secure offtake agreements before breaking ground; investors can finance capacity expansions against futures curves instead of hoping for signed contracts.

Whichever structure wins, the dominant players will be those who can hold inventory risk across heterogeneous assets, verify performance at scale, and manage the energy exposure underlying every compute contract.

Trading, Hedging, and Where Basis Risk Hides

If compute becomes tradable (even partially), several strategies emerge.

Energy-compute correlation trades become especially interesting once both markets are liquid. Power is a primary input for data centers (often 30-50% of operating costs), which means compute prices should track electricity forwards closely. But if the compute forward curve lags movements in regional power markets (say, Texas summer peaks or renewable curtailment events), traders can exploit that basis by buying cheap compute forwards and hedging with power futures. This is analogous to the “crack spread” in oil (where refiners hedge crude inputs against refined product outputs) or “spark spread” in power generation. Data center operators with fixed power contracts could use the inverse trade to lock in margins.

Arbitrage plays show up wherever standardization is incomplete. Suppose H100 and B200 hours are theoretically interchangeable for inference workloads, but the market hasn’t priced that equivalence correctly. An aggregator could buy cheap B200 capacity, repackage it as “inference-grade compute,” and sell it at H100 prices. Or imagine a firm noticing Virginia data centers consistently trade at a premium to Oregon because most buyers default to US-East-1. It buys Oregon capacity, sells Virginia exposure, and pockets the basis.

Calendar arbitrage becomes possible once forward curves exist. A hyperscaler might lock in cheap off-peak capacity six months out, knowing demand spikes are predictable (end of quarter, model release cycles). Or a quant fund could trade the spread between spot and three-month forwards, betting on mean reversion in utilization rates.

The trickier part is basis risk (the residual uncertainty that can’t be hedged away). In compute, that includes chip equivalence (are B200s really 1.2× H100s for your workload?), latency and locality (can you actually move your job to a cheaper region?), queue time and preemption risk, and energy passthrough (if power prices spike, does your contract adjust?). Those risks are real, but they’re also tradable if the market defines them clearly.

Constraints: Physical and Regulatory

Even with elegant market design, physical and regulatory constraints shape what’s possible.

Physical realities: Data centers need power, cooling, land, and transmission infrastructure, all with long lead times. A liquid spot market might reveal that Northern Virginia is 30% more expensive than West Texas, but if the fiber backhaul doesn’t exist or the grid can’t handle another gigawatt, that price signal can’t clear the imbalance. The market can only allocate what’s already there or credibly coming.

Regulatory uncertainties: If compute futures trade on an exchange, who regulates them (the SEC, the CFTC, or someone new)? If capacity auctions allocate data center time the way FERC oversees power markets, do we need a “Federal Compute Regulatory Commission”? And if a few hyperscalers control most of the supply, does that create market-power concerns similar to electricity generation? These questions aren’t hypothetical: antitrust enforcers are already scrutinizing AI infrastructure, and clear rules will matter as much as clever auction design.

Where the Market Goes and Where to Build

So where does this leave us? Here are three hypotheses worth testing, each paired with signals to watch and opportunities to pursue.

Hypothesis 1: Expressive auctions are the practical on-ramp. Standard specs (chip class, memory, interconnect) plus combinatorial bidding can unlock liquidity without pretending all compute is identical. Watch for: multi-attribute bundles (e.g., “H100 OR B200, Virginia OR Oregon”) outgrowing single-SKU trades. The Auctionomics-OneChronos platform will be the first real test of whether this framework scales. Meanwhile, SF Compute and Compute Exchange (founded by Don Wilson, who pioneered modern derivatives trading at DRW) are testing simpler models: hourly rentals and periodic auctions. If these platforms see sustained volume and participants start publishing bid-ask spreads, it signals the market is ready for more sophisticated mechanisms. Build: Verification and oracle infrastructure (who certifies performance specs?), scheduling and clearing systems (how do you match buyers and sellers across time and geography?), and energy-compute coordination tools (how do you hedge power exposure?).

Hypothesis 2: Aggregators with balance sheets win the mid-term. Buyers want simplicity and reliability; sellers want utilization and price discovery. Aggregators who can hold inventory risk, wrap SLAs into standardized products, and provide two-sided liquidity will capture value before full commoditization arrives. Watch for: specialized providers (CoreWeave, Lambda) starting to act like market-makers (buying excess capacity, reselling it, and publishing bid-ask spreads). Early examples like Spot.io, which monitors and optimizes cloud costs, hint at this model. Build: Balance-sheet-backed resellers, regional exchanges with local clearing, and analytics platforms tracking basis curves, and power-price correlations.

Hypothesis 3: Hyperscalers will tolerate (or enable) liquidity if it derisks their capex. AWS, Azure, and GCP have pricing power today, but they also have massive capital commitments and utilization risk. A transparent market could let them hedge future demand, finance new capacity against forward curves, and compete more surgically without broad price cuts. Watch for: incumbents participating in or sponsoring exchange infrastructure (the way utilities backed ISOs). If AWS lists capacity on a neutral venue, that’s a strong signal that liquidity serves their interests. The big unknown is whether they see compute as a high-margin product (protect the moat) or a high-volume commodity (compete on execution). Their behavior will tell us which future we’re in. Build: Platforms for hyperscalers to list excess capacity, analytics tracking pricing behavior, and partnerships reducing counterparty risk.

Later, derivatives venues, index providers (a “compute VIX”?), synthetic exposure products, and cross-commodity desks (power ↔ compute arbitrage) all become possible once spot and forward markets are liquid. You could even imagine capacity developers financing new data centers via hedged offtake agreements, the way renewable energy projects use PPAs. This is an exciting future, but the rails need to be built first.

Conclusion: Markets Make the Future

Full commoditization of compute might never arrive; heterogeneity, locality, and security will always matter. But partial standardization can still unlock liquidity, better planning, and cheaper innovation. We’ve seen it work for oil, power, and spectrum. There’s no reason compute can’t follow a similar path, as long as we respect the complexity and build the right mechanisms.

The design choices are still up for grabs. Will it look more like power markets, with expressive auctions and ancillary services? Or shipping, with containerized units and regional basis? Or oil, with deliverable grades and financial hedging? That depends on what builders, operators, and policymakers choose to prioritize and what signals the early market sends.

Either way, the opportunity is real. Compute is already one of the largest unhedged assets in the global economy. If we can turn it into a tradable one, the capital will follow, and the AI boom will have the financial rails it needs to scale. Let’s build them together.

References and Additional Reading:

Primary Sources

Salmon, Felix. “The AI Boom Needs a Market for Compute, Just Like Oil and Spectrum.” Bloomberg, September 26, 2025. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2025-09-26/the-ai-boom-needs-a-market-for-compute-just-like-oil-and-spectrum

“Auctionomics and OneChronos Partner on First Tradable Financial Market for GPU Compute.” Business Wire, July 29, 2025. https://www.businesswire.com/news/home/20250729678918/en/Auctionomics-and-OneChronos-Partner-on-First-Tradable-Financial-Market-for-GPU-Compute

Market Platforms

SF Compute. “H100s with 3.2Tb/s InfiniBand.” Accessed November 2, 2025. https://sfcompute.com

Compute Exchange. “GPU Compute on Your Terms.” Accessed November 2, 2025. https://compute.exchange

News Coverage & Analysis

Kinder, Tabby. “’Absolutely immense’: the companies on the hook for the $3tn AI building boom.” Financial Times, August 14, 2025. https://www.ft.com/content/efe1e350-62c6-4aa0-a833-f6da01265473

Osipovich, Alexander. “AI Needs a Lot of Computing Power. Is a Market for ‘Compute’ the Next Big Thing?” The Wall Street Journal, January 29, 2025. https://www.wsj.com/tech/ai/ai-needs-a-lot-of-computing-power-is-a-market-for-compute-the-next-big-thing-2302133c

Brown, Aaron. “Computing Power Is Going the Way of Oil in Markets.” Bloomberg Opinion, February 24, 2025. https://www.bloomberg.com/opinion/articles/2025-02-24/computing-power-is-going-the-way-of-oil-in-markets

Chapman, Lizette. “Jack Altman’s Firm Backs Startup for Trading AI Computing Power.” Bloomberg, July 16, 2024. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2024-07-16/jack-altman-s-firm-backs-startup-for-trading-ai-computing-power

Griffith, Erin. “The A.I. Industry’s Desperate Hunt for GPUs Amid a Chip Shortage.” The New York Times, August 16, 2023. https://www.nytimes.com/2023/08/16/technology/ai-gpu-chips-shortage.html

Company Announcements

“Compute Exchange Launches to Transform How AI Compute is Bought and Sold.” Business Wire, January 29, 2025. https://www.businesswire.com/news/home/20250128536805/en/Compute-Exchange-Launches-to-Transform-How-AI-Compute-is-Bought-and-Sold

Further Reading on Market Design

Auctionomics. “About Auctionomics.” https://www.auctionomics.com/

OneChronos. “About OneChronos.” https://www.onechronos.com/